Pushing Back Against Global North’s Outer Space Monopoly: An Asean-India Approach

The Global South would be risking its rightful place in the cosmic frontier if ASEAN, India and other emerging space nations do not act now.

Shreyasree Paul/India

Introduction to Regulatory Arbitrage in Space

The outer space, which is otherwise conceptualised as a “common heritage of mankind,” has fallen into the control of select influential nations. Whereas the Outer Space Treaty (OST) protects it from sovereign appropriation, we can see a new bias against the Global South through ‘appropriation-by-proxy,’ evading these foundational principles. Simply put, these nations bring forth their private players to lay hold of common resources by exploiting the lack of appropriate binding laws. Such actions incite regulatory arbitrage, which roughly translates to the strategic exploitation of disproportions between the economic and legal atmospheres of any two countries. It is this difference that becomes a tool for legitimizing what the Outer Space Treaty was designed to prevent.

Increasing Monopoly and Market Concentration in Outer Space from a Competition Law Perspective

Statistically, SpaceX alone holds approximately 60% of the global launch capacity, whereas the distribution of geostationary orbital slots favours other Western nations, courtesy of the Bogotá Declaration, 1976. Furthermore, the 2015 US Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act and the Luxembourgian Space Resources Law, 2017, bestow private entities with more authority over cosmic resources, which leads to commercialising said “global commons.” Such interference makes one question the effectiveness of Articles II and VI of the OST (national appropriation and state responsibility, respectively). Since there is no clear proof of commercial activities equating to national appropriation, unchecked monopolies are created and justified by the same “global commons” logic. From a competition law perspective, the current space economy is heavily influenced by monopolistic practices. Where essential commodities such as orbital parking spaces, control stations, communication systems, etc., should be accessible to everyone, it gets hoarded by developed nations.

These implications create an unfair competition for the early spacefaring nations, making research and development an even harder feat to pursue. Deployments of mega-constellations, such as Starlink’s utilization of thousands of orbital slots, contribute to such inequity. This situation mirrors the 1976 Bogotá Declaration, in which equatorial countries challenged the unfair allocation of geostationary orbital resources, a warning that continues to be ignored in present space governance. If such inequity persists, resolving these monopolistic issues stands to become more futile.

🔺Fig. 1: SpaceX’s Starlink at its fifth Integrated Flight Test (IFT-5).

Countering “Appropriation-by-Proxy” in Outer Space Through ASEAN-India

The Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Indian space economy from the Global South are speculated to be strong contenders to the aforesaid monopolistic regime. (ASEAN-India Relations). Both parties bring an array of technical and institutional capabilities to make them competent leaders in the Global South and thereby increasing their collective bargaining power.

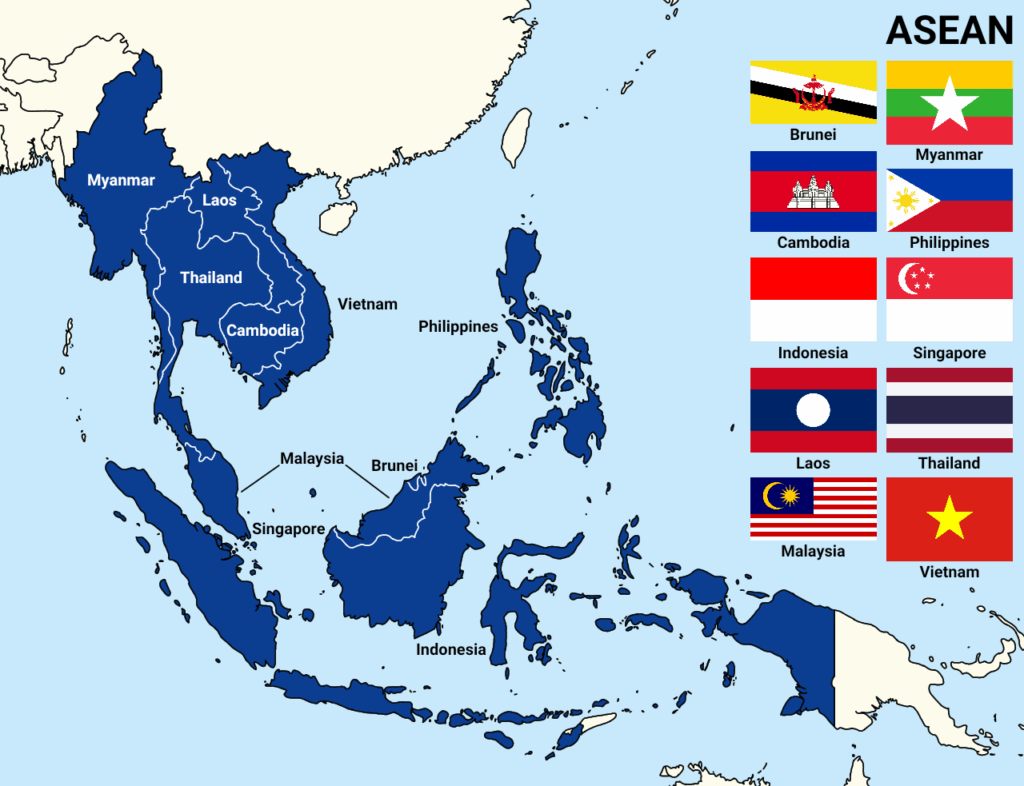

ASEAN is characterised by diversity, which is an irrefutable advantage within the regulatory debate on governance in space. Singapore is the regulatory and sustainability centre of the region, having established strong governance infrastructures. Indonesia has engaged through ORPA to harness both its demographic and economic weight to provide institutional coordination in the region around remote sensing and earth observation, making it a leading nation in space exploration. Vietnam has established ties to Japan, the EU, and ISRO, and has an enviable record of satellite development. Malaysia and its ANGKASA programme, and MEASAT commercial telecommunication network, with Thailand’s GISTDA, have established earth observation support for disaster monitoring. The Philippines has PhilSA and is developing Diwata microsatellites, which emphasises how a smaller state can specifically innovate around survivability, especially in the aftermath of a disaster. Although Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Brunei are less developed, they lend geographic coverage and political mass to ASEAN’s consolidated voice.

Fig.2: List of ASEAN countries

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) channels its prowess in cost-effectiveness and technical proficiency through its various missions, such as the Mars Orbiter Mission, Chandrayaan-3, Aditya-L1, etc. These missions were accomplished at a budget that equates to a fraction of what Western nations spend on their space missions. Additionally, under the most recent National Budget, the government has endowed a venture capital of 1000 crore rupees, which proves its trust in ISRO’s competency, commercial development, and technological advancements.

What would the ASEAN-India Collaboration yield?

When brought together, these attributes uniquely empower ASEAN-India to become a powerful coalition to resist monopolization and promote the Global South’s interests in the future of space. Much like how EU competition law revolutionized digital administration. Instead of waiting for international amendments, which are vetoed by the Global North, this collaboration should create a regional space framework that also honours competition law principles, such as mandatory technological data transfer, mutual orbital slot negotiations, pre-decided profit-sharing ratios on the proceeds from space resource extractions, and enhanced sanctions on policy violations. Not only would this create cordiality between the member states, but also promote economic measures against the monopolistic practices, as discussed earlier. That is to say, it could also end the roots of appropriation-by-proxy and regulatory arbitrage.

🔺Fig. 2: ASEAN-India collaboration at the ASEAN Secretariat @Jakarta, 2025.

Naturally, such an optimistic revolution would not occur overnight, given the realistic shortcomings, such as tariff asymmetries between these nations, trade agreements, cultural barriers, and so forth. As stated earlier, with passing time and zero action to tackle said Global North’s advances, it would only become more difficult to resolve these inequalities. The Global South would be risking its rightful place in the cosmic frontier if ASEAN, India and other emerging space nations do not act now.

***

Shreyasree Paul is Final Year Student, B.COM.LL.B. (Hons.), Presidency School of Law, Presidency University, Bangalore, India and Intern at Centre for Air and Space Policy (CASP)- shreyasreepaul03@gmail.com