Can Private Companies Go to Space? Here’s How the Law Sees It

Private companies launch satellites, build rockets, plan lunar missions, and sell space-enabled services that power daily life on Earth. The idea of “commercial space” is no longer futuristic. It is operational. But space is not a legal free-for-all, even when the actors are private.

So, can private companies go to space? Yes.

Can they do it however they want? No.

International space law is built on a simple structure: space is a shared domain, states remain responsible, and private activity is allowed only through state authorization and supervision.

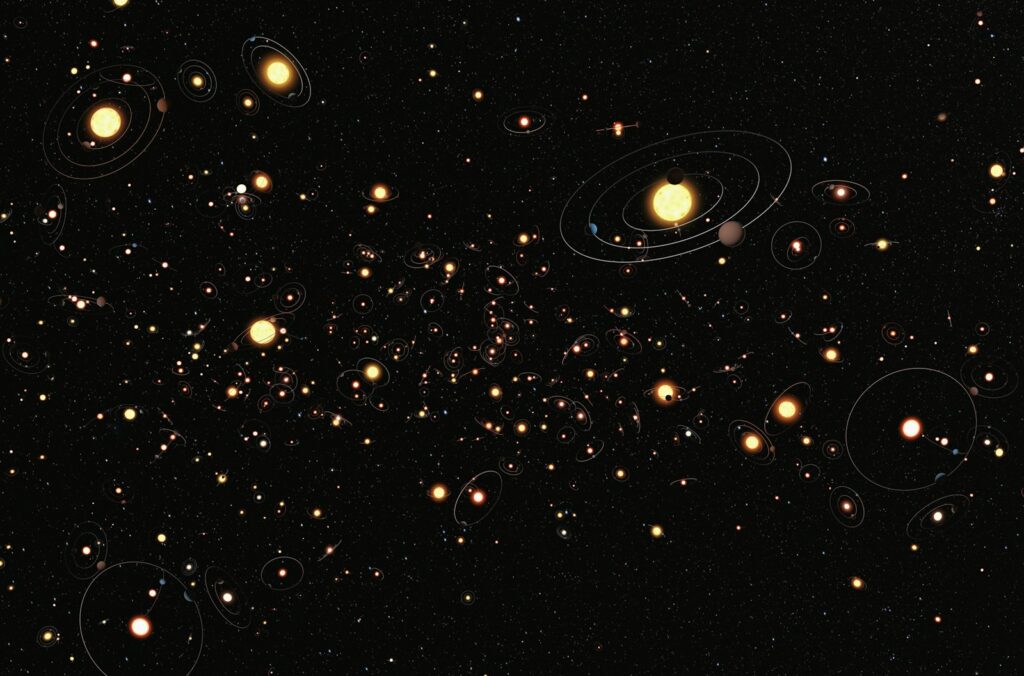

Space Is Not a Place You Can Own

The starting point is one of the most important principles in space law: outer space is not subject to national appropriation. States cannot claim sovereignty over the Moon, a planet, or a slice of orbit in the way they claim territory on Earth.

This principle matters for private companies too. If a company launches a spacecraft, it does not gain territorial rights in space. Space is not a real estate market, no matter how hard some people may try to turn it into one.

But that does not mean nothing can be owned. Space itself is not owned as territory, but space objects are. Satellites, spacecraft, and equipment are property under national law and contracts. What is restricted is the idea of claiming space as territory.

The Legal “Trick”: Private Companies Operate Through States

The core way international law handles private space activity is by routing responsibility through states. Under widely accepted principles, states bear international responsibility for national space activities, whether those activities are conducted by government agencies or private companies.

That means private companies do not operate in a legal vacuum. They operate in a legal chain:

Company → National license/authorization → State responsibility under international law

This is why almost every serious commercial space actor needs some form of national licensing. States authorize launches, supervise operators, and set conditions on safety, liability, insurance, and compliance.

What “Authorization and Continuing Supervision” Really Means

One of the most practical legal requirements in space law is that private space activities must be authorized and continually supervised by the appropriate state.

In real terms, this usually involves:

- licensing for launches and reentry (where relevant)

- safety and operational approvals

- insurance requirements and liability allocation

- registration processes for space objects

- rules on frequency use and interference avoidance

- oversight mechanisms for compliance and incident reporting

“Continuing supervision” is the part many people ignore. It is not a one-time permission slip. It is ongoing accountability, especially important as satellite constellations become larger and more complex.

Liability: When Space Objects Cause Damage

Space activities carry unusual risks. A space object can cause damage in space (to another satellite) or on Earth (if debris falls). International law contains rules about responsibility for damage caused by space objects, and these rules influence how states design national licensing and insurance requirements.

For private companies, liability is not just a legal concept. It is a business reality. Insurance costs, risk assessments, and compliance obligations are shaped by the legal expectation that damage can create state-level responsibility and operator-level financial consequences.

Crowded Orbits, Debris, and the Sustainability Problem

One of the biggest challenges for commercial space is not permission to operate. It is the condition of the environment itself.

Low Earth orbit is increasingly congested. More satellites mean more collision avoidance maneuvers, more debris risk, and more operational coordination needs. Debris mitigation, end-of-life disposal, and transparency are now central to responsible space activity. Even if the law does not always impose strict enforcement globally, the policy direction is clear: sustainability is becoming a baseline expectation for legitimacy.

For companies, sustainability is not charity. It is self-preservation. If key orbits become unsafe, the market becomes more expensive and less viable for everyone.

What About Mining the Moon or Asteroids?

This is where things get controversial. International law strongly resists territorial sovereignty claims. But resource use raises a harder question: if no one can own the Moon, can anyone own what they extract from it?

Different legal interpretations exist, and states have taken different approaches in national law and policy. The debate is still evolving, and it is likely to remain a major issue as technology advances. What is clear is that commercial ambitions are pushing the law into areas that older treaties did not fully anticipate.

So What Does the Law “See” When It Looks at a Private Space Company?

International law does not treat private companies as fully independent space actors in the way it treats states. Instead, it tends to “see” them through their sponsoring state’s responsibility and supervision.

This creates both opportunity and constraint:

- companies can operate and innovate, often faster than governments

- but they must do so within a legal framework built around state accountability and shared-use principles

The system is imperfect, but it has a purpose: prevent space from becoming an unmanaged domain where accidents and conflicts scale without control.